Life and achievements

Early life

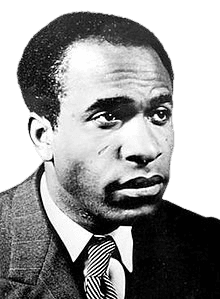

Frantz Fanon was born on July 20, 1925, in Fort-de-France, Martinique, a French colony in the Caribbean. Raised in a middle-class family, Fanon was one of eight children. His father was a customs officer, and his mother was of Afro-Caribbean and French descent. Growing up in Martinique under French rule, Fanon experienced the harsh realities of colonialism and racism from an early age. He attended the prestigious Lycée Victor Schœlcher, where he was influenced by his teacher, the renowned poet and politician Aimé Césaire. Césaire’s ideas about Black identity and anti-colonialism left a lasting impression on Fanon, who would later expand on these themes in his own work.

During World War II, Fanon joined the Free French forces at the age of 18, fighting in North Africa and Europe. He was awarded the Croix de Guerre for his bravery but was disillusioned by the rampant racism within the French military, where Black soldiers were segregated and subjected to discrimination. This experience deepened Fanon’s awareness of the oppressive structures of colonialism and inspired him to explore the psychological impact of racism. After the war, Fanon moved to France, where he studied medicine and psychiatry at the University of Lyon. His exposure to existentialist philosophy, psychoanalysis, and Marxist theory shaped his intellectual development, and he began to write critically about race and colonialism.

Legacy

Frantz Fanon’s legacy as a revolutionary thinker and anti-colonial theorist continues to influence social and political movements across the globe. His works, particularly Black Skin, White Masks and The Wretched of the Earth, remain foundational texts in post-colonial studies, critical theory, and liberation psychology. Fanon’s ideas about the psychological effects of colonialism, the role of violence in liberation, and the importance of reclaiming one’s humanity through resistance have inspired generations of activists, scholars, and revolutionaries.

Fanon’s emphasis on the dehumanizing effects of colonialism and his call for violent resistance to achieve liberation resonated with anti-colonial movements in Africa, Latin America, and Asia throughout the 1960s and 70s. His work provided intellectual justification for armed struggles against colonial powers, influencing groups like the Black Panther Party in the United States and the National Liberation Front in Algeria, where Fanon was actively involved. His concept of the “colonial world” as a divided space—where colonizers and the colonized exist in fundamentally opposed realities—continues to shape discussions on global inequality, race, and systemic oppression.

Fanon’s revolutionary vision was not limited to the physical decolonization of nations but also extended to the psychological and cultural liberation of oppressed peoples. He warned against the dangers of neocolonialism, where former colonies would remain economically dependent on former colonial powers, and he emphasized the need for radical social transformation. His work remains a powerful critique of colonialism’s lingering impact on post-colonial societies and the ongoing struggles for racial and economic justice.

Milestone moments

Jun 28, 1952

Publication of Black Skin, White Masks

In 1952, Fanon published Black Skin, White Masks, his first major work, which delved into the psychological effects of colonization on Black individuals.

The book examined how colonialism dehumanizes the colonized, forcing them to internalize feelings of inferiority and adopt the culture of the colonizer, while being excluded from full participation in it.

This publication established Fanon as a leading voice in anti-colonial thought, offering a profound analysis of race, identity, and alienation in a colonial context.

Mar 18, 1959

Joining the Algerian War of Independence

In 1954, Fanon became involved in the Algerian War of Independence after being stationed in Algeria as a psychiatrist. He joined the National Liberation Front (FLN) and began actively supporting the anti-colonial struggle.

He used his position in the hospital to provide psychological treatment to both Algerian freedom fighters and French soldiers, witnessing firsthand the brutal effects of colonial violence.

This marked a turning point in Fanon’s life, as he became not just a theorist but a revolutionary, deeply involved in the struggle for Algerian independence.

Oct 18, 1959

Publication of A Dying Colonialism

In 1959, Fanon published A Dying Colonialism, which analyzed the Algerian Revolution’s impact on the cultural and social structures of Algeria.

Fanon described how the revolution transformed long-standing cultural practices and led to a collective identity forged through resistance against French colonial rule.

This book highlighted Fanon’s deepening engagement with the Algerian struggle, portraying the revolution as both a political and cultural awakening.

Aug 14, 1961

Publication of The Wretched of the Earth

In 1961, Fanon published his most influential work, The Wretched of the Earth, just months before his death. The book called for the violent overthrow of colonial regimes and critiqued the limitations of non-violent resistance.

Fanon argued that decolonization was inherently violent and that this violence was necessary for colonized peoples to reclaim their humanity and overthrow oppressive systems.

This work cemented Fanon’s status as a revolutionary thinker, influencing liberation movements around the world, from Africa to Latin America and beyond.