Life and achievements

Early life

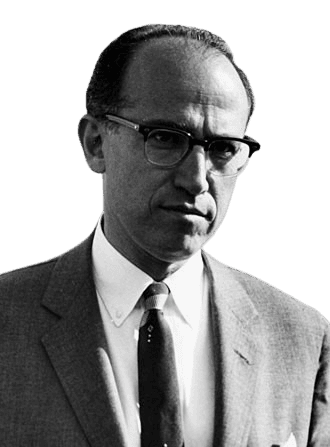

Salk was born in New York City on October 28, 1914, into a family of Jewish immigrants. His parents, Daniel and Dora Salk, were simple frictional farmers without formal education but wanted their children to become good students. Since early childhood, Salk has been fond of reading books, and he studied well at school due to his desire to gain knowledge.

He was educated at Townsend Harris High School, the school for gifted; he received his chemical education at the City College of New York. He first trained to become a lawyer but changed his mind and went to New York University School of Medicine.

When Salk was studying at NYU, he developed an interest in medical research, specifically virology. He was fortunate to be under the tutelage of Dr. Thomas Francis Jr. The first significant work done by Salk was the research to develop a vaccine for the flu that was instrumental in World War II.

This experience provided a basis for Salk's work in polio cases because he was convinced that the killed-virus vaccine could be used for other diseases.

Legacy

There can be no doubt that Jonas Salk left a vast legacy – and this in terms of both the polio vaccine and the philosophy of science and medicine. His discovery of the inactivated polio vaccine was a milestone in the war against one of the most dreaded diseases of the 20th century.

Salk's vaccine had subsequently led to a decrease in polio cases globally by 1960, and he was not interested in patenting it to make profits—Salk's belief in putting public interest before personal gain strongly influenced medical morality and vaccine production.

In 1963, Salk established the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California, where many of the most eminent scientists and researchers have come to work in genetics, immunology, and neuroscience. The institute's working model and emphasis on cross-disciplinary research result from Salk's conviction that science should be used to satisfy humanity's wants.

His later work comprised research on aging, cancer, and autoimmune diseases, as well as developing an HIV vaccine during the 1980s and 1990s.

In addition to his scientific impact, Salk's personality, when in the public eye, helped the general public embrace science. He was their hero, especially during the polio epidemics of the 1950s, and his life experiences motivated generations of scientists. Salk was also a staunch supporter of compulsory vaccination, saying that it is immoral to expose children to diseases that could be prevented. He carried out work that would later benefit future vaccine successes and is still a reference for current health policies.

Milestone moments

Nov 2, 1947

To assume the position of the Director of the Virus Research Laboratory at the University of Pittsburgh

In 1947, Jonas Salk joined the University of Pittsburgh as the Director of the Virus Research Laboratory, where he began working on the poliovirus.

Polio was a terrible disease then, especially for children, and the search for a vaccine had become a top priority across the world.

Salk's appointment let him concentrate on preparing a vaccine that he advocated killed-virus vaccines.

This position was the starting point of his work, which would culminate in one of the most significant medical discoveries of the twentieth century.

Aug 31, 1953

August 31, 1953, marked the first human trials of the polio vaccine and Jonas Salk's first success.

Finally, in 1952, Salk decided to test his inactivated polio vaccine on his family members, his wife and children, and some people from the D.T. Watson Home for Crippled Children.

The first experiments showed that the vaccine does not have severe side effects and may be effective, so the next step was a national test in which over one million children participated and were called 'polio pioneers.'

These trials prepared the way for the mass use of the vaccine and may be considered the starting point in the gradual victory over polio.

Jun 12, 1955

The vaccine against polio was declared safe and effective.

The Salk polio vaccine was officially declared safe and effective on April 12, 1955, after the extensive tests were completed.

It was received with joy since the vaccine held a promise of victory against polio, a disease that paralyzed thousands of children annually.

The vaccine's effectiveness ensured that millions of children in the United States and other parts of the world received it within a few years.

May 16, 1959

Polio Vaccine Reaches 90 Countries

By 1959, Salk's vaccine had been supplied to nearly ninety countries, drastically decreasing polio cases worldwide.

Most countries in Europe and the Americas embarked on mass immunization, and the vaccine was instrumental in the global fight against polio.

This milestone showed the world how Salk's work affected the global society and became a significant triumph for global health.