Life and achievements

Early life

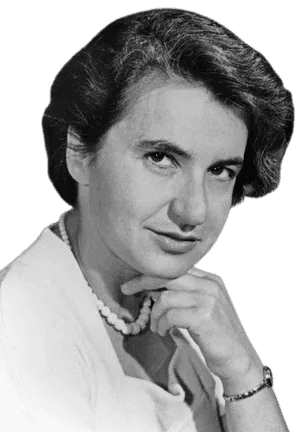

Rosalind Elsie Franklin was born to a wealthy and prominent Sephardic Jewish family in Notting Hill, London. Her father, Ellis Franklin, was a banker and a politician, while her mother, Muriel Franklin, belonged to a rich family. From early childhood, Franklin was a bright child who performed well in school, especially in mathematics and sciences. She went to St. Paul's Girls' School, one of the few schools in London that offered higher sciences for girls at that time. Franklin received a good education in this environment; she was good in physics, chemistry, and Latin and had a lifetime passion for learning.

In 1938, Franklin joined Newnham College, Cambridge as a chemistry student. She had a chance to meet several famous scientists at Cambridge that would impact her early work. She completed her course in 1941 and passed with second-class honors, equivalent to a bachelor's degree. She stayed at Cambridge briefly before joining the British Coal Utilisation Research Association and doing her PhD work there. Her thesis on the structure of coal was followed by several papers and offered background information for further research on porous materials.

Franklin's post-World War II stay in Paris was critical to her scientific personality. Franklin, who joined the Ray Department in 1947, learned X-ray diffraction techniques under Jacques Mering, a French crystallographer. These skills were essential when she moved back to London in 1951 to work at King's College London, where she started working on DNA.

Legacy

Rosalind Franklin can be remembered as a great scientist, but she was not recognized as much as she deserved during her lifetime. Her work on the structure of DNA paved the way for the discovery of the double helix, even if her work was initially overlooked and credited to Watson, Crick, and Wilkins. However, historians, scientists, and the general public have come to recognize Franklin's essential contribution to molecular biology.

Therefore, Franklin's legacy is not just in DNA. Her later work on viruses, especially TMV and poliovirus, was pioneering and formed the basis of most of the current-day virology. Her passion for science in light of her terminal illness showed her spirit and her pursuit of research. Franklin was also a role model for women in science. She worked in a man's world and demonstrated that women can perform complex scientific research, and her life story is a symbol of women scientists in the middle of the twentieth century.

Today, many people know Rosalind Franklin as a woman who contributed to the development of science. Her work has been fundamental in studying the structure of DNA, RNA, and viruses and has significantly impacted the field of genetics and the creation of new treatments. She is known as a great scientist and the first woman to have worked in chemistry, physics, and biology. In her honor, several awards, scholarships, and institutions have been established to motivate the upcoming generations of scientists.

Milestone moments

Jul 1, 1945

PhD from Cambridge: Breakthrough in Coal Research

Rosalind Franklin received her PhD from Cambridge in 1945 after researching the physical chemistry of coal.

Franklin's thesis was conducted at the British Coal Utilisation Research Association, where he looked at the microstructure of coal and how it responds to conditions like temperature and pressure.

Her work showed how coal's structure impacted its permeability and application in industrial uses such as gas mask filtration during the war.

These early studies revealed Franklin's ability to analyze data, and it was her first exposure to X-ray diffraction, a method she would later master in her DNA work.

Her work was valued, and she published several papers that were still relevant in material science dealing with coal.

The knowledge she gained in the structure of carbon materials provided her with an excellent background for her subsequent work involving DNA and viruses.

Gaining her PhD was a significant achievement in Franklin's early career, indicating her graduation from a promising student to an accomplished scientist with expertise in X-ray crystallography.

This technique was critical to her later success.

Feb 14, 1947

Postdoctoral Research in Paris: Controlling X-ray Crystallography

In February 1947, Franklin started postdoctoral work at the Laboratoire Central des Services Chimiques de l’État in Paris with Jacques Mering, a famous French crystallographer.

This was a significant period in her work as Franklin developed a mastery of X-ray crystallography, a method she would later employ to study DNA.

Mering taught Franklin more sophisticated X-ray diffraction methods, which she used to analyze structures of carbon and graphite.

Her work provided a new understanding of atoms' structure in carbonaceous materials and advanced the field of material science.

Franklin's increasing mastery of this work and its accomplishments led to her being acknowledged as an expert in X-ray crystallography; she authored several papers in this field during this period.

Franklin received many new opportunities and valuable lessons in Paris, which influenced her life and work.

Her stay in Paris cemented her position as a skilled and precise scientist and paved the way for her transfer to King's College London, where she would use her crystallography to analyze DNA.

Her stay in Paris was one of the most important stages in her evolution into one of the leading researchers in the field of structural biology.

May 1, 1952

Photograph 51 Captured: The Key to DNA's Structure

In May 1952, Rosalind Franklin took what would turn out to be one of the most iconic X-ray diffraction images ever taken—Photograph 51.

This picture was captured at King's College London during the research of DNA structures, and it offered the most evident proof of DNA's double helix structure.

Franklin's painstaking studies on DNA's "B" form, the biologically active form, showed an X-shape pattern that indicated the helical structure of the molecule.

Franklin used X-ray crystallography to identify the structure of DNA through the diffraction patterns of fibers.

"Photograph 51" was the most significant discovery because it best illustrated the DNA helix structure.

However, Franklin's work was disclosed to James Watson and Francis Crick without her permission, and they developed their now-famous model of DNA in early 1953.

This moment is one of Franklin's most important scientific accomplishments, but she received credit for it after her death.

Today, "Photograph 51" is recognized as a milestone in the discovery of the structure of DNA and as evidence of Franklin's indispensable but unacknowledged contribution to the history of molecular biology.

Mar 6, 1953

The Last Word on DNA Structure

By March 1953, Franklin had amassed enough evidence to establish that DNA was helical and the strands twined in a double helix.

In her research notes and a series of drafts of her paper for Nature, she explained how her X-ray diffraction studies of the 'A' and 'B' forms of DNA supported the spiral model.

Franklin did not construct models of the physical kind, as did Watson and Crick, but her empirical data corresponded to the structure they suggested.

Franklin's work helped to determine that the phosphate groups of the DNA molecule were on the outside while the bases were packed inside, a significant piece of the puzzle in understanding the molecule.

Her work appeared in Nature just a year after the publication of Watson and Crick's paper, offering experimental evidence for the proposed model.

This is Franklin's penultimate discovery before she can reveal the structure of DNA.

If Franklin had not been having her research published without her consent, she might have made the final leap herself.

Her role in this scientific discovery is now crucial to discovering the double helix.