Life and achievements

Early life

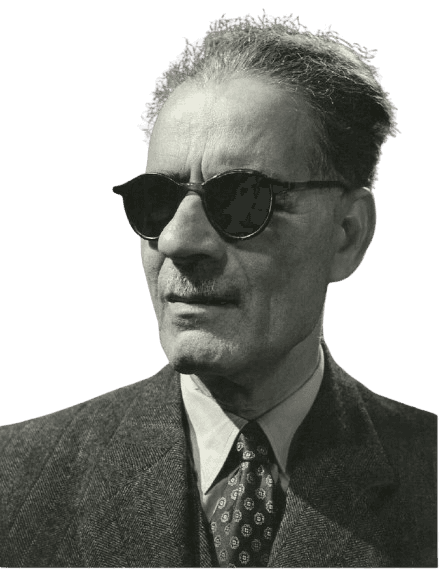

Taha Hussein was born on November 14, 1889, in the village of Maghagha in the province of Assiut in Upper Egypt. Childhood and youth were characterized by the low-income family in which the subject was the seventh of thirteen children. When Hussein was two years old, he developed ophthalmia, an eye disease that was treated wrongly and caused him to become blind.

He could have been a hopeless case, having grown up blind in a rural village, but his parents wanted him to attend school. He started his education at a local kuttab, a religious school where children learn to memorize the Qur’an, and even with his disability, he proved to be a child prodigy.

Hussein proceeded to Al-Azhar University in Cairo, one of the oldest and most recognized universities in the Islamic world. However, he was disappointed with the conservative and traditional approach to teaching at Al-Azhar. He began to seek knowledge in other ways, and in 1908, when Cairo University was established, he joined it. His stay at Cairo University was the defining moment of his life because he embraced modernism and was interested in provoking change in literature and education.

Legacy

Taha Hussein’s contribution is not limited to literature but extended to education, politics, and social change. He was the Egyptian Minister of Education in 1950 and introduced measures that transformed the Egyptian educational system; he insisted on free education as a fundamental human right. His famous quote, “Education is what we need as much as the air we breathe and the water we drink,” indicates that he wanted education to be available to all, irrespective of the social and economic status of the learner.

This policy formed the basis of education development in Egypt, especially public education, and has impacted the lives of millions of Egyptians.

Hussein’s literary contribution is also enormous. His works are some of the most important in modern Arabic literature, especially his autobiography Al-Ayyam. His style of writing included elements of his own life, and yet, at the same time, his topics were general enough for people from all over the Arab countries to relate to. Hussein was also an active participant in the Arab Renaissance (Nahda) movement aimed at liberalizing Arab culture and education in the struggle against colonialism and obscurantism. As a critic, he revolutionized how Arabic literature was read by calling for the modern and critical reading of texts.

Taha Hussein’s contributions to Arabic literature and thought are still being lauded. He was a fearless critic of the norms of society and believed in education as a means of liberation, which made him a legendary figure in Arab intellectual history. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature twenty-one times, proving the significance of his impact and the acknowledgment of his works internationally. Today, he is remembered as one of the greatest Egyptian intellectuals of the century who triumphed over personal misfortunes to enlighten the generations with his words and thoughts.

Join Confinity and create a lasting digital legacy, just like history’s greatest minds. Signup Now

Learn how this historical figure’s legacy continues to shape our world today →

Milestone moments

Nov 14, 1889

Birth of a Literary Giant

Taha Hussein was born in 1889 in Maghagha, Upper Egypt, to a large but not very wealthy family. His childhood was difficult, mainly because he became blind after he contracted an eye infection that was left untreated when he was only two years old.

Nevertheless, his parents developed his intellectual capacity by supporting him in going to school. At six, he was sent to a religious school to memorize the Qur’an, as was the tradition for boys in rural Egypt.

It gave him a good base of Islamic traditions that he would later reject most of as he grew up. His childhood predetermined his struggle against ignorance and poverty throughout his life. Blindness was never a barrier to Hussein’s quest for knowledge and education; it made him more determined to rise against all odds society placed in his way.

Jul 17, 1908

Admission to Cairo University

1908, when Hussein was enrolled at Cairo University, he was introduced to ideas. Being one of the university’s first students, he faced new ideas that opposed the traditionalist teachings of Al-Azhar, which he attended before.

This change from religious to secular education expanded Hussein’s horizons to modern literature, philosophy, and social change. His studies made him doubt not only the premises of Arab literature but also the structures of Egyptian society.

Cairo University equipped Hussein with the conceptual apparatus to start questioning tradition, a concept that would preoccupy him in his later years. While at the university, he also read Western literature and philosophy, which shaped his writing.

Jun 9, 1914

First Ph.D. at Cairo University

This was a significant achievement for Taha Hussein and the university since he was the first student to graduate with a Ph.D. from Cairo University in 1914. His thesis was on the blind poet and philosopher Abu al-Ala al-Ma’arri, whose earlier works were acclaimed in Arabic literary circles.

Hussein chose Al-Ma’arri as the poet for his thesis; this was a personal decision, as the author saw himself as the poet. Both men had been blind since childhood and employed their disability to search for the ultimate philosophical meaning.

This accomplishment was to be Hussein’s first official introduction into the sphere of Arabic literary criticism. It also prepared the ground for his later attacks on much of traditional Arabic poetry and literature as inauthentic, as he then started questioning the genuineness of much of the pre-Islamic poetry that was sacred to the Arabs.

Mar 14, 1926

On Pre-Islamic Poetry is published

Pre-Islamic Poetry, published in 1926, can be considered a turning point in Hussein’s career. The book raised the issue of the genuineness of much early Arabic poetry, arguing that it had been tampered with or fabricated for political and tribal gains.

This bold critique of one of the most revered aspects of Arab cultural heritage angered religious scholars and traditionalists. Some people accused Hussein of blasphemy, and the book was burnt. It was republished later with some changes, but the ideas of this work remained important for literary critics and historians.

Nevertheless, Hussein stood his ground, unyielding to the controversy surrounding his rule. He argued that he had the right to challenge the past and that no tradition should be sacred to anyone. This made him both friends and foes but cemented his position as a courageous philosopher.